Frida Kahlo’s paintings show pain, they are a reflection of her miserable life. And yet they were very well known and taught feminism to many people.

Whether you know Frida Kahlo by her famous artworks, her immaculate style or as a feminist icon. There was one thing that truly made her stand out: She forced people to look at her and her art, to share her feelings and suffering, when they would prefer to look away.

A Life Beginning With Suffering

Magdalena Carmen Freida Kahlo y Calderón was born in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City, in July, 1907. Frida’s father, Guillermo Kahlo, was German-born and among his five daughters, Frida was said to be his favourite. She was a very spirited child, playing many pranks on her sisters and stealing fruit from nearby orchards. That changed when she contracted polio at age six.

Frida was confined to her bed for nine-months, after which her father prescribed her to sports. She was excellent in many sports, like soccer, swimming, roller-skating and boxing, causing her to grow stronger, even though her right leg remained small and withered. This gave her the name „peg leg” in school, so to treat her loneliness, her father gave her books from his library and taught her how to take and develop photos.

When she was fiveteen, Frida enrolled in the prestigious Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, where she focused mostly on biology, hoping to become a doctor one day. She was a bright and engaged student, belonging to an elite club of brains and mischief-makers, the Cachuchas.

Only Art Remained for Her

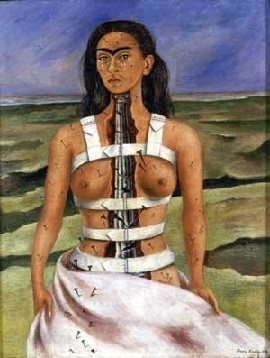

On September 17, 1925, Frida and her boyfriend were riding home from school on the bus when it was hit by a streetcar. She was impaled by a handrail that entered her just above her left hip and exited through her vagina. Her back and pelvis were each broken in three places. Her collarbone was broken too, her right leg fractured and her smaller foot dislocated and mangled. Someone thought it was a good idea to pull out the handrail before the ambulance arrived. Frida’s screams and the sounds of bone cracking, were louder than the approaching sirens.

For a month Frida lay in a plaster body cast, no one expecting her to survive. When she was released from the hospital, the treatment was bed rest, months of bed rest. The medical bills piled up, and her father mortgaged the house to pay them. Her life of chronic pain began.

The next year, a new set of doctors examined her spine and realised the first set of doctors had failed to see that several vertebrae had healed incorrectly. This would become a running theme and the solution: another plaster body cast and more bed rest.

After the accident, flat on her back in bed, painting presented itself as one of the only activities available to her. She pretended not to care about the quality of her work, but in 1927, once she was able to walk, she sought the professional opinion of the celebrated artist Diego Rivera.

Love Life Disaster

Frida and Rivera were both members of the Mexican Communist Party, and Rivera was captivated by Frida’s character. She was one of those tiny women who could drink men twice her size under the table. She lived on a diet of candy, cigarettes, and a daily bottle of brandy, causing her teeth to rot in early middle age. On cause of this, she ordered two sets of dentures: one solid gold, another studded with diamonds. As anyone who’s ever purchased a Frida tote bag, postcard, coffee mug, or T‑shirt knows, she was proud of her unibrow and her moustache, which she kept neat with a small comb reserved for that purpose.

In August 1929, Frida and Diego were married. Frida was a somewhat sheltered 22-year old and Rivera was a 43-year old established artist, with two ex-wives. During the first years of their marriage when Frida, presumably, happily performed the role of exemplary wife. She devoted herself to cooking for her husband, fussed over his clothes and comfort, gave him his nightly bath in which she floated bath toys for his amusement. Her husband was a giant baby.

Rivera had many affairs and when caught, would explain patiently that for him monogamy was simply out of the question, and that he viewed sexual intercourse as essential and uncomplicated as taking a piss. Frida would howl in fury, hurling the occasional ceramic plate against a brightly painted wall, then lock Rivera out of her bedroom. He would retaliate by throwing himself into his latest mural commission, and maybe take on another mistress or two. Sometimes, upon discovering the identity of the new mistress, Frida would enjoy a little revenge by seducing the woman. Then they would have another argument in which Frida hurled another ceramic plate, and so on and so forth.

The Making of an Independent Career

In the summer of 1938, at the age of 31, Frida made her first sale. The actor Edward G. Robinson was also an art collector, and while he was in Mexico City, he purchased four little pictures, for $200 a piece. French artist André Breton also discovered her work, and heralded it as surrealist. Her paintings, he enthused, were like „a ribbon around a bomb”. One might think, her discovery would be a great moment for Frida, but she wasn’t much interested, she found the French to be cold and bourgeois. She was her own movement.

In the same year, Frida had her first solo exhibition in New York, at the Julien Levy Gallery. There, she met a rich woman, who offered her money for Frida to paint a tribute to her friend who committed suicide. What was expected definitely wasn’t delivered. Frida drew her friend jumping from a building and land on the ground, with a broken neck and blood flowing form her head. The banner along the painting reads: „In the city of New York on the 21st day of the month of October, 1938, at six o’clock in the morning, Mrs. Dorothy Hale committed suicide by throwing herself out of a very high window of the Hampshire House building. In her memory [a strip of missing words] this retablo, executed by Frida Kahlo”.

Imagine the shock of the woman. Frida did what she was best at, expressing her heart in every brushstroke.

Frida and Politics

In 1939, Frida and Diega Rivera were divorced, due to Rivera choice of having an affairs with Frida’s sister, Cristina. Several years later, Trotsky and his wife arrived in Mexico City to live with them, having been expelled from the Soviet Union.

Trotsky and Rivera would argue politics. Trotsky and Frida would have a fling, sending Madame Trotsky into an understandable depression. Trotsky escapes several assassination attempts by Stalinist operatives dispatched from the Soviet Union, only to be murdered on August 20, 1940, by a demented local man with an ice ax.

Frida and Diego, now living separately, were both suspects. Rivera fled to San Francisco, while Frida was taken into custody for questioning. She was released after a few days, and also left for San Francisco to consult Dr. Leo Eloesser about some kind of chronic fungal infection. Eloesser had treated her for various maladies in 1930, and had become a trusted friend. In San Francisco, Frida and Diego got back together, remarrying in 1940 at a small civil ceremony.

Using Pain as an Artistic Device

Artists have different sources that they use to gather inspiration. Frida seemed to require a careful mixture of despair at Diego’s disappearing acts, loneliness, and active engagement with her own broken body. To date, her complete medical history remains unknown. She is said to have had 30 surgeries over the course of her lifetime, most of them attempts to repair the damage from the bus accident she’d suffered at 18. She saw a round of doctors, most of whom contradicted each other. Mexican doctors once declared she had „a tuberculosis in the bones” and wanted to operate. Dr. Eloesser disagreed. In 1944, her chronic back pain worsened.

In the first part of 1946, she sought out a well known to perform a complicated surgery in which four vertebrae were fused using bone from her pelvis. Her recovery was a success, but eventually she suffered again from shooting pains. A new doctor in Mexico examined her and claimed the New York doctor had performed the fusion on the wrong vertebrae.

Frida’s bone grafts developed infections, requiring painful injections. Her circulation suffered so much from inactivity and a terrible diet that one day she woke up to find that the tips of the toes on her right foot were black. Eventually, they were amputated, followed by her leg, amputated below the knee in 1953, a year before she died. Some of Frida’s most certifiable masterpieces came from the excruciating time in her life, for example „The Broken Column” (1944) or „The Wounded Deer” (1946).

When Frida died in 1954 at the age of 47, she was known primarily as Diego Rivera’s exotic little wife. The rise of feminism in the late 1970s brought with it the question „Hey, where are all the women artists?, Where are all the women of color?” and the answer was the rediscovery of Frida Kahlo.

Feminism Displayed in Art

Fifty-five of Frida Kahlo’s 143 pictures are self-portraits. Many of them depict the difficulties of living in a human female body, including female reproduction and its, sometimes occurring, failures. Metal hospital beds, bloody instruments, a snarl of internal organs she seems to be vomiting in despair. A delicate, anatomically correct image of her own heart beating inside her chest, her naked body splayed open, giving birth to her adult self. The female nude, so beloved of fine artists, had never been nude like this.

Then as now, it’s a well-known truism that men are uncomfortable when women cry. One can only imagine how squirmy they must have been, how squirmy they are, in the presence of Frida’s pictures. But Frida was a woman comfortable among the chaos of her feelings. She never denied them, never dialed them down. It made her strong. Or, in the view of some difficult.

Kennst du schon Takashi Murakami? Seine Werke sind mehr als Kunst, sie sind Nachrichten an sein Publikum.